Preparing low worm-risk paddocks

.jpg/Zz0zNDRlNmZlMjBlYmMxMWYwOTk5YzVlMmQ3Njg2YmYwZg==)

Preparing low worm-risk paddocks to prevent sheep from heavy worm burdens is a key strategy in effective and profitable worm control. This article covers strategic preparation methods for lowering the worm-risk of paddocks.

Preparing low worm-risk paddocks to prevent sheep from heavy worm burdens is a key strategy in effective and profitable worm control.

A paddock is considered “low worm-risk” if it has such a low level of infective worm larvae that when sheep, treated with an effective drench before their move, are introduced, it takes a few months before worm numbers build up to levels that cause illness.

Strategic preparation of low worm-risk paddocks for different classes of sheep can reduce production loss and the need for chemical intervention, i.e., drenches. Fewer drenches mean reduced costs, less labour and slower development of drench resistance. There can also be benefits to other classes of sheep due to fewer worms on-farm overall.

There are three methods for lowering the worm risk of pastures:

- Allow time for most of the eggs and larvae on the pasture to die

- Avoid paddocks heavily contaminated with worm larvae

- Reduce contamination of paddocks with worm eggs

Note that there is a risk that drenching sheep onto low-worm pastures may increase drench resistance levels alike summer drenching.

The main need for low-worm pastures in Western Australia is in winter and spring for weaners and lambing ewes. This is because the hot, dry conditions in summer prevent larval survival, and pasture growth is generally not sufficient to support significant larval development until at least May.

The level of worm risk of a paddock varies greatly because it depends on the level of contamination before the paddock was spelled. In a moderately to heavily contaminated paddock, generally about 95% of worm larvae need to die for it to be considered low-worm-risk.

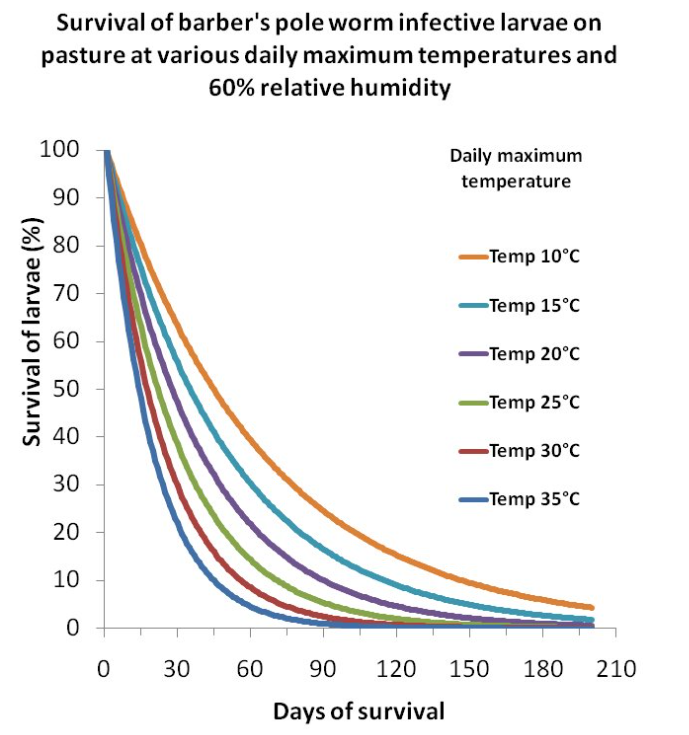

As an example, the following graph shows the rate at which barber’s pole worm larvae die. This is quite similar for scour worms. Choose the temperature line that fits your location in the few months before a low worm-risk pasture is required and find where larval survival (left side of graph) drops to 5% to indicate the number of days required for 95% of larvae to die.

Source: Paraboss (modelled based on the findings of Barger, Benyon & Southcott (1972))

Low worm-risk paddocks can be prepared, particularly in the South-West Medium to High Rainfall zones where worm problems are common, by preventing contamination of pastures with worms in the 3-4 months before you want to use them (i.e., during autumn-winter) through:

- Spelling the paddocks from sheep and instead grazing with cattle or using them for crops, hay or new pasture establishment

- Grazing the paddocks with sheep that have been tested for worm egg count with a result of less than 200 epg. Note that this is not appropriate in coastal areas where barber’s pole worm is a concern

Spelling for 3–4 months in spring or autumn results in about 90% or more worm larvae dying. Spelling for less than two months is not enough for a low worm-risk pasture, and spelling for 4 months is only required if spelling includes winter months, when larvae take longer to die.

Another important aspect of grazing management, where possible, is to avoid grazing the most susceptible sheep (i.e., weaners and lambing ewes, especially maidens, twin-bearing ewes and those in poorer condition) in the highest worm-risk paddocks in winter and spring (i.e., those that have been grazed by wormy sheep or sheep that are 2 years of age or younger).

You can find more information on worm control, specific to your region, at wormboss.com.au

Source: Paraboss

- Preparing Low Worm-Risk Paddocks for Sheep - WormBoss

- Grazing Management for Sheep in Western Australia Winter Rainfall Region - WormBoss

Amy Lockwood, AWI Extension WA

.png/Zz0yM2JiZjM5ODBlYmMxMWYwOTU5YTYyNTc0YTA0ZjBjZQ==)